How do microbiomes respond to environmental chemical exposure?

Gut microbiota modify environmental chemicals, altering bioavailability

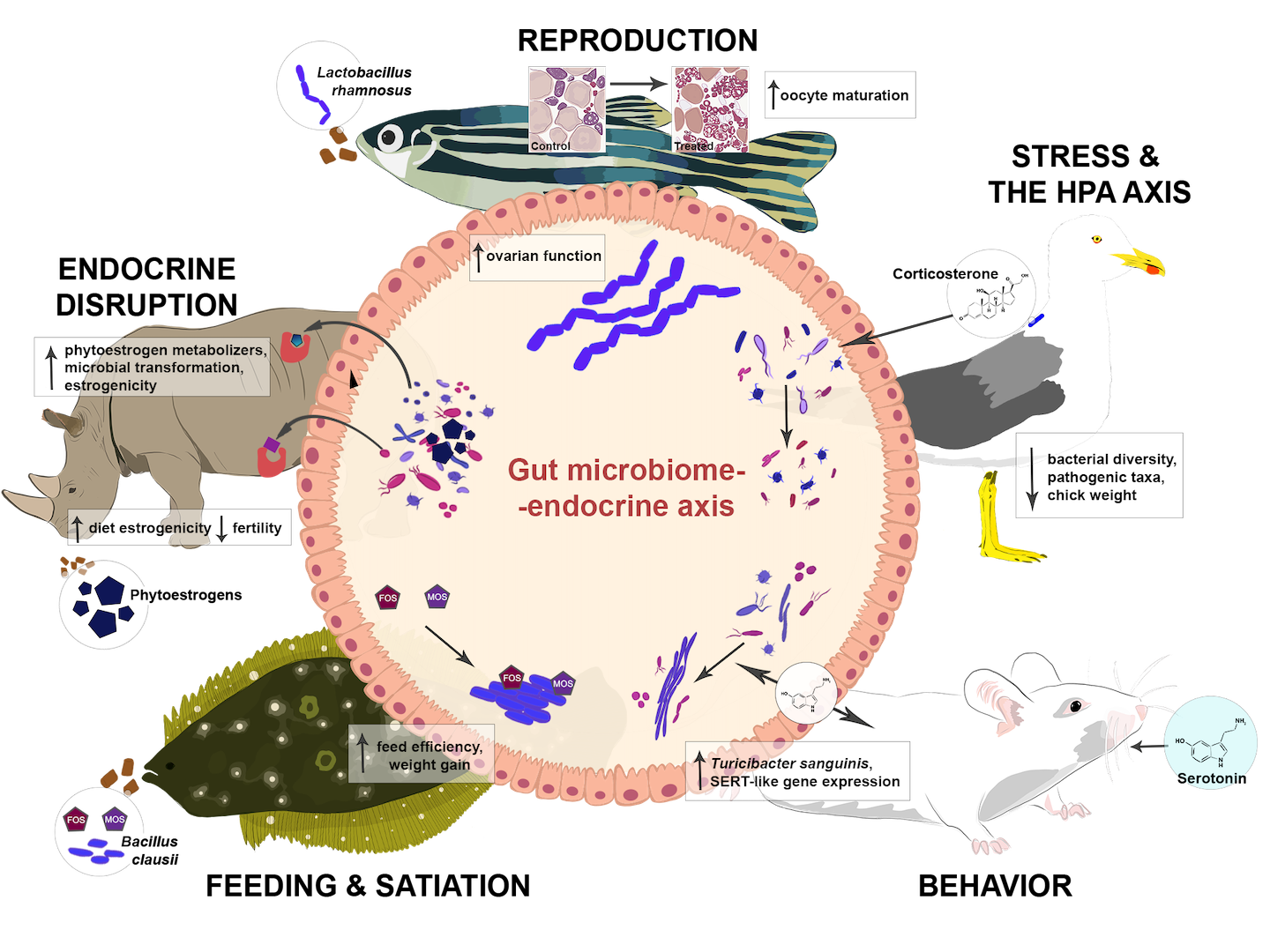

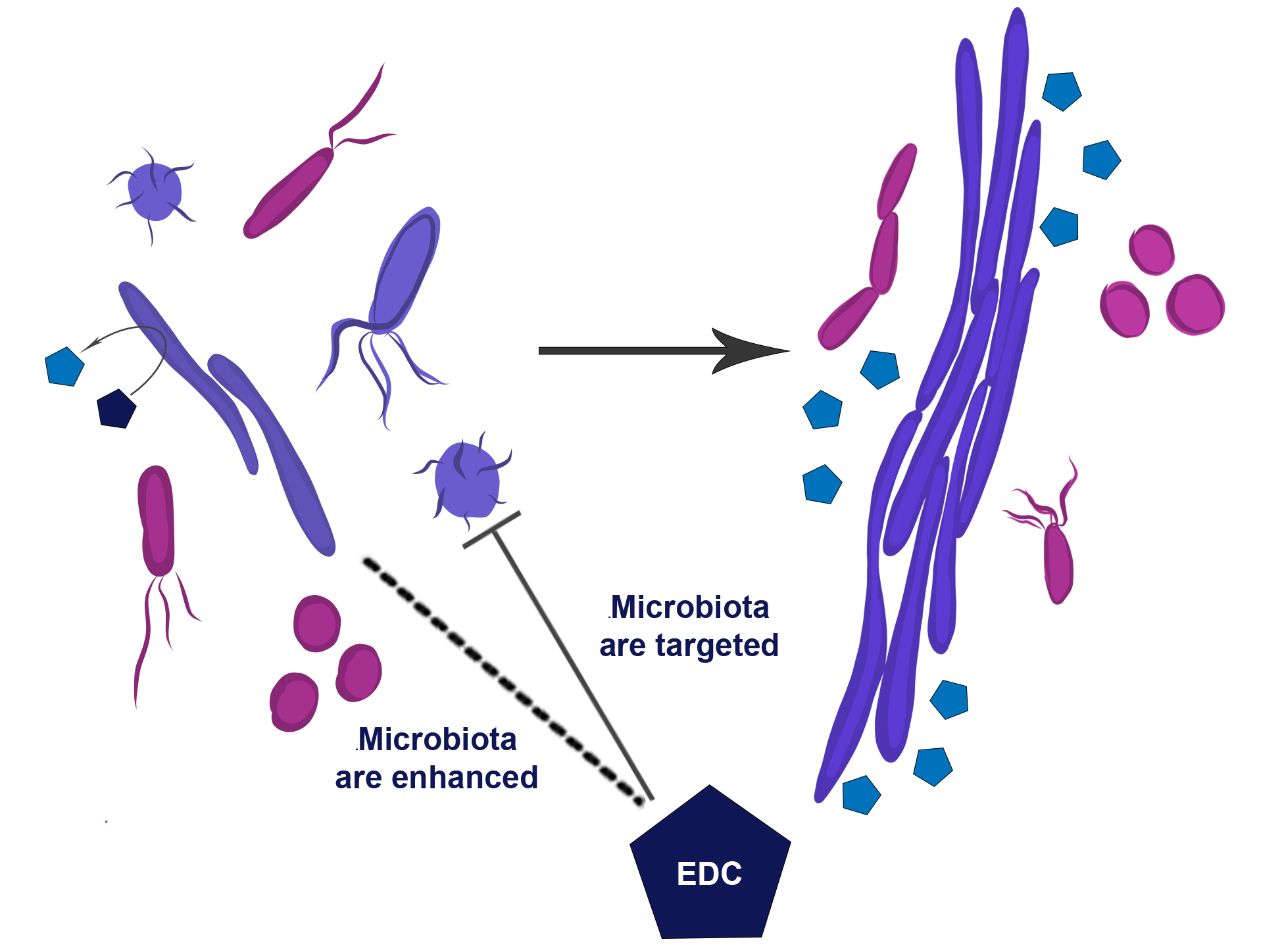

Industrialization and urbanization have led to increased exposure to environmental chemicals, and are in turn linked to a multitude of adverse health outcomes. Some environmental chemicals are synthetic, including persistent organic pollutants, pesticides, and synthetic pyrethroids, and plasticizers. Yet, some are naturally occurring, like heavy metals that are anthropogenically dispersed or phytoestrogens, whose abundance can be exacerbated by our warming planet. When environmental chemicals come into contact with gut microbiota following ingestion, they can directly target or modify microbiota, leading to reduced bacterial diversity and other systemic effects. Additionally, microbiota can also influence exposure severity through chemical transformations that alter environmental chemical activity [1].

Insight into the microbial mechanisms driving animal fitness

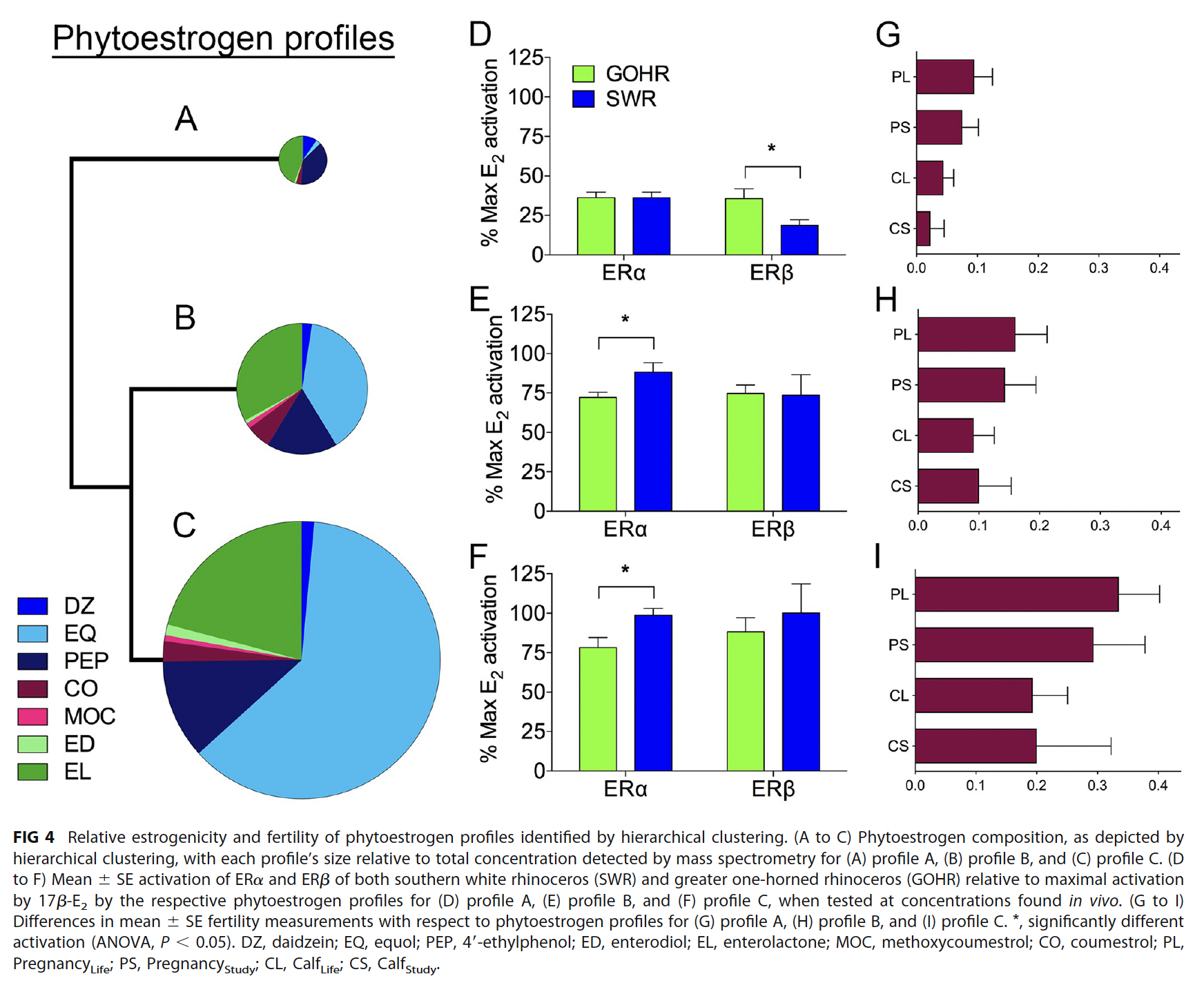

Some environmental chemicals are excellent endocrine disruptors, whereby their structural similarity to hormones can lead to adverse effects either organizational or activational means, but the mechanism of action is not always well understood. For example, wild-born rhinos do not display lowered fertility when fed a high phytoestrogen diet, but those born in captivity do. Yet, when phytoestrogen consumption is reduced in captive-born animals we have observed increased fertility in some individuals, but not all. We have shown that sensitivity of rhino estrogen receptors to some phytoestrogens varies in vitro [2], but when in combination, as observed in vivo, they elicited varying levels of estrogenicity across profiles in vitro, with one combination of phytoestrogens exhibiting greater estrogenicity than estradiol itself. Additionally, these phytoestrogen profiles strongly correlate to fertility. We also observed phytoestrogen transformation by the gut microbiota in vivo via opportunistically collected serum and feces and in vitro through heavy water incubations and Raman microspectroscopy. These data demonstrate that white rhinos are an informative model, as their phenotype aids in understanding the relationship between phytoestrogens, microbial transformation, endocrine disruption, and reproductive outcomes.

Expected societal impact

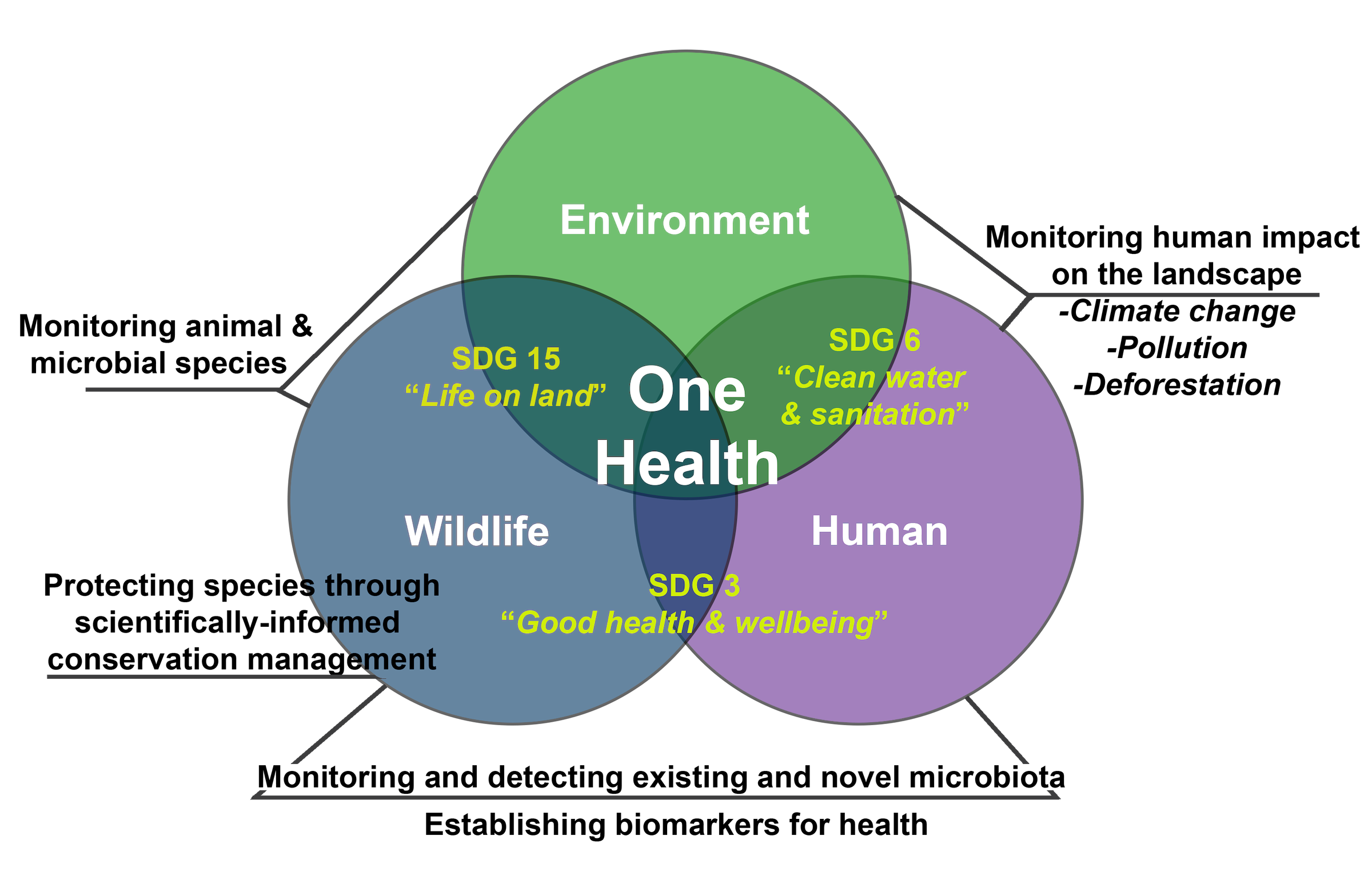

This work is uniquely positioned to support the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals through a One Health approach (SDGs). First, we must protect/prevent biodiversity loss and extinction of threatened species (SDG 15). Due to numerous anthropogenic threats, the need for captive wildlife management exists, ranging from assist-rearing offspring who are orphaned or rejected to genetic reservoirs for species facing imminent extinction. For many threatened species, captive-reared offspring destined for release are necessary to recover wild populations. My work examines microbiota and its relationship with host health at this intersection, aimed at examining how microbes relate to reintroduction success and evaluating the potential to enhance these efforts by rewilding microbiota as we rewild species into their natural habitats or better care for them in captivity. With > 42,000 species currently under threat of extinction, < 1% of these species’ microbiomes have been evaluated [4], it is imperative that we expand our scope beyond human-centric studies. Second, the application of the proposed work promotes other sustainability efforts. One example is investigating the mitigation potential of microbiota in reducing severity of pollution/contaminants (SDG 3 & 6). In our growing anthropogenic landscape, contaminant exposure is increasing, and unravelling the mechanisms that drive both negative and positive outcomes in hosts will lead to the identification of microorganisms that can mitigate host effects in vivo, or better still, be used in ecosystem wide bioremediation efforts.

Other related work

- Environmental chemical exposure and the vulture microbiome, in collaboration with Caroline Moore (SDZWA), Jasper Chao, and Mónica Medina (Pennsylvania State University).

- Contaminant impacts and the recovery of mountain yellow-legged frogs, in collaboration with Spencer Siddons, Caroline Moore, Natalie Calatayud, and Debra Shier (SDZWA).

- The METSI project - Dynamics of cyanobacteria and toxin production across gradients in hydroclimate and elephant pressure on water pans in Botswana, in collaboration with Lihini Aluwihare, Jeff Bowman, and Kenosi Kebabonye (Scripps Institution of Oceanography), Caroline Moore (SDZWA), and Mosimanegape Jongman (Uni. of Botswana).

References

- Williams CL, Reyero N, Tubbs CW, Martyniuk C, Bisesi JH (2020). Microbiome-endocrine regulation: Perspectives from comparative animal models. Gen. and Comp. Endocrinology, 292: 113437.

- Williams CL, Ybarra AR, Meredith AN, Durrant BS, Tubbs CW. (2019) Gut microbiota and phytoestrogen-associated infertility in southern white rhinoceros, mBio 10(2) e00311-19.

- Williams CL et al. (2022) Adaptation to captivity drives rapid changes in the rhinoceros gut microbiome. International Symposium on Microbial Ecology ISME18.

- Williams CL, Caraballo-Rodríguez AM, Allaband C, Zarrinpar A, Knight R, Gauglitz JM (2019). Wildlife-microbiome interactions and disease: exploring opportunities for disease mitigation across ecological scales, Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models, 28: 105-115.